Elevating the Profession: Issues and Perceptions of Early Childhood Education By: Emily Lian, M.Ed

“Oh, you work in a preschool- that’s fun! You must have a lot of patience. What do you think you’ll do when you start looking for a real job?” I’ll never get over that sting, because I hear it often. I meet strangers who think my job is “cute” because I write curriculum for a preschool franchise. I overhear parents referring to our centers as a “daycare” and it makes me visibly cringe. We oftentimes hear about the plight and struggles of K-12 teachers, yet the work of preschool teachers is frequently belittled. Early childhood education clutters the bottom of the education totem pole with misconstrued mental images of coloring pages, cupcakes, and dramatic play costumes. How did we get here, and where do we go from here?

Let’s begin by considering the etymology of this word, “daycare”.

Essentially, it’s a place where working families can place their children during the “day” to be “cared for”. Makes sense, right? Except, we aren’t in the business of growing children like a plant. Our work is much more complex than just caring for children, even though we share this love for every child who walks through our doors. Research in recent decades has pointedly concluded that the first five years of a child’s life are crucial for their brain development. Additionally, families have shown a marked spike in prioritizing academically focused programs when selecting a preschool for their children so they are prepared for primary school. That being said, curriculum and instruction are vital to running this kind of program- which I daresay sounds more like a school than a place you drop your child off for someone to change their diaper and feed them while you go to work.

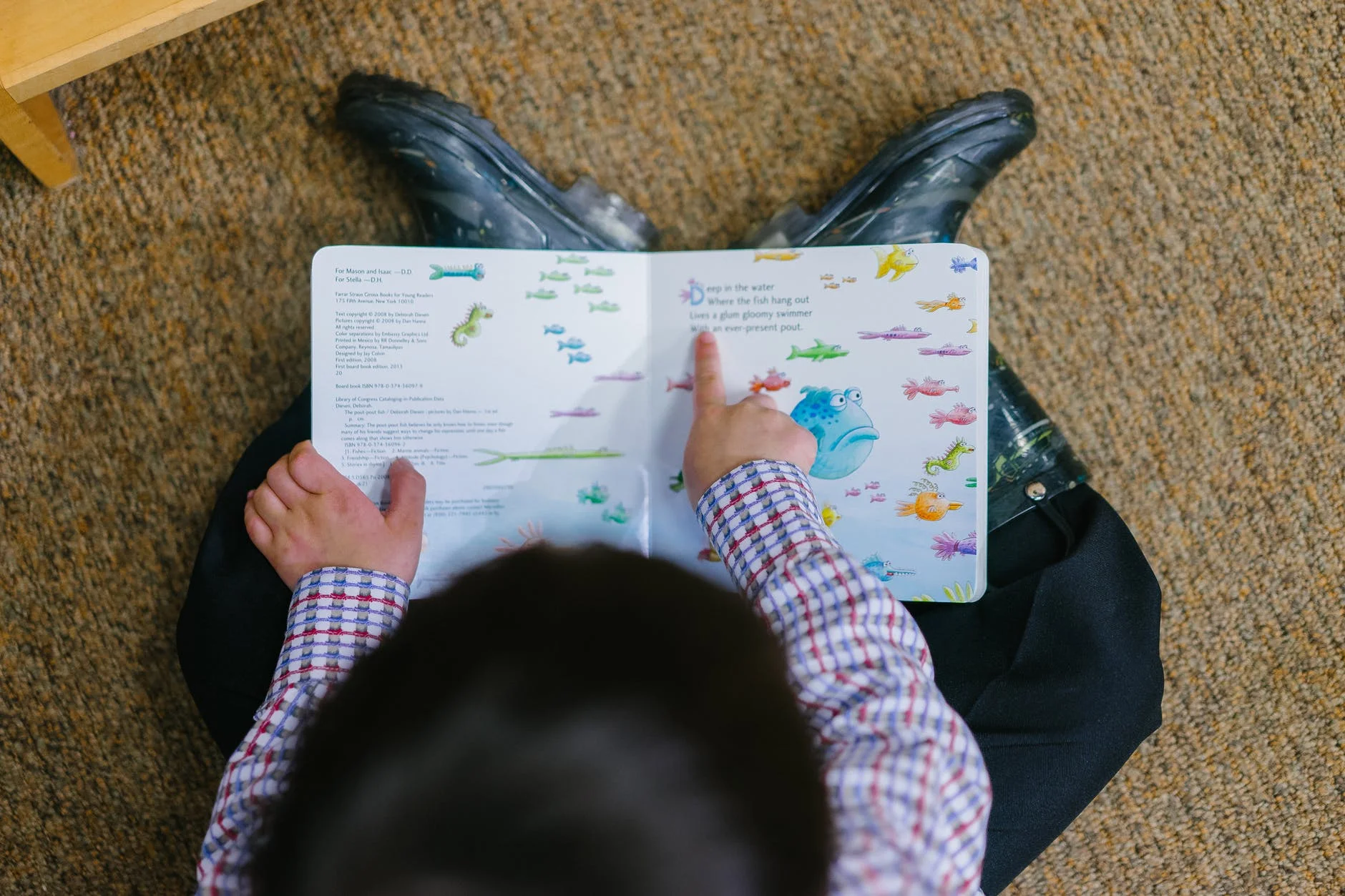

Speaking of what a school looks like…

Working in this field is fraught with challenges. Regardless of whether the program provides a curriculum or requires their teachers to create their own lesson plans, the expectations for early childhood educators are suspiciously similar to K-12 teachers. The learning objectives may not be as complicated, but the work is no less important. They still have to follow a schedule, prepare for lessons ahead of time, scaffold activities to introduce new concepts, differentiate instruction for children who may need accommodations, assess students on a regular basis, employ a variety of classroom management techniques, properly utilize technology to supplement lessons, host parent-teacher conferences… all while receiving significantly lower pay than their educator counterparts, little or no benefits, and oftentimes having to work with high classroom ratios.

Who makes up the workforce in early childhood education?

I’ve spent the last several years learning about the challenges of adult learning on an intimate, first-hand basis. Intrinsic motivation has always been a significant factor in the success of professional development opportunities. I’ve generally found a combination of three distinct types of teachers and administrators who attend trainings: the ones who have to be there to complete mandatory training hours but will spend an inordinate amount of time in each session texting or chatting with the person next to them, the ones who want what I call a “magic wand” solution to their very specific challenges, and the ones who are genuinely open to learning new things from a fresh perspective. The first type of teachers are the ones that I struggle with the most. After all, how can you inspire and teach young minds when you don’t recognize that learning never stops for you, either?

In my experiences, I’ve met teachers from so many different educational backgrounds. Of the various centers I’ve worked for, our staff includes young teachers who are going to school for completely unrelated degrees, certified teachers who are biding their time while looking for a job in a school district, and older teachers who thought that working with children would be an easy, stress-free post-retirement plan. What’s stressful about reading stories and doling out hugs all day, right?

Therein lies the first problem: for many preschool teachers, this is a means to an end.

They might love children and they might have enough adorable anecdotes to fill a book, but there’s a lack of true motivation to elevate the field itself. A very small percentage of college graduates decide that the menial pay of a preschool teacher is worth their four-year degree. We represent a workforce that isn’t something children grow up dreaming about joining.

It’s so easy to become inundated with the day-to-day challenges of being in a classroom or a center. In the same hour in a single morning, a teacher might deal with a bathroom accident, an escape artist who is trying to break out of the classroom, AND an emotional child who had a rough drop off. But, she is still expected to follow her posted schedule and teach letter and number recognition to a class of children whose moldable minds are very susceptible to learning something from every interaction they encounter. When teachers are just trying to make it through a day, how can we ask them to spend more time putting new policies into action, devote personal time or weekends to attend trainings, and happily accept their meager paycheck while privately owned preschool owners line their pockets with profits?

And, here’s the second problem: the people in power.

Many early childhood education administrators (directors, assistant directors, curriculum coordinators, education directors) were promoted from teaching positions. That being said, how long as it been since some of the more seasoned leaders stepped foot in a classroom with students they were directly responsible for? From an administrative perspective, running a preschool is more like running a business. There are bills to be paid, tuition to be collected, payroll to be completed, schedules to be moved around to maintain ratios, meetings with upset parents who pay an arm and a leg to send their child to the center… and that’s just to name a few. How many administrators find the time to connect with their teachers as frequently and as deeply as they would like to? How many administrators are able to set aside managerial duties to connect with who we are all here for: the children?

I’ll throw another wrench into the mix: who are the people making and enforcing these systemic issues? How many preschool owners decided to open up a center based on their own experiences working in early childhood education? How many preschool owners saw the opportunity for a cash cow, because this field is such a necessity for working families? Who were the people in power who created high classroom ratios? Have they ever toilet trained a classroom of 22 two year olds (the maximum group size for this age group in Texas)? My intention here is not to throw the entire upper management team under the bus, but in order to have a frank discussion about elevating the profession we have to think about the layers of disrespect that permeate throughout the field. How can we hope to garner more respect for early childhood education, if the people signing our paychecks have never felt the injustice of being called a glorified babysitter? How can we advance this field, if leaders don’t value the efforts and contributions of their workforce?

What can we do? In my ideal scenario, there would be an entire system overhaul.

In a perfect world, I would demand significantly elevated pay and benefits for the workforce. I would demand higher hiring qualifications, where not anyone with any kind of degree can just walk in and begin working with children because a center is struggling with staffing shortages. Here’s the final big one (which is especially prevalent in the United States): I would demand a widespread shutdown of privately owned preschools. Or, at the very least, laws that required preschool owners to have working experience in the field, not just money and a little bit of entrepreneurial acumen. Education is society’s crucial weapon to survive and thrive, and early childhood education is no less important than the rest of the years of schooling a child will move through in their lifetime. When profit margins become the priority, it is clear that student outcomes take a backseat to collecting as many monthly tuition checks as possible.

But, considering the unrealistic parameters of my utopian dream, I’ll settle for greater respect.

It is impossible to make early childhood education visible and respected, if the people within the field do not view their jobs as vital. Teachers need to respect their own profession, in order to promote it. Better training processes should be explored to properly introduce teachers to their roles and to inspire them to adopt a growth mindset as a professional. Adequate support should be provided to navigate day-to-day challenges, and reflective opportunities should be prioritized. There is an entire culture of mutual trust and respect that is required to create a psychologically safe workplace, one where teachers are motivated to try new approaches to their instructional practices. Mentorship programs should be enacted to encourage teachers to elevate themselves into leadership roles. Professional development should not be viewed as a compliance check box, but rather as an opportunity to network, connect, and learn.

While I speak from my own personal experiences, I know that these issues are widespread.

We deserve more than a condescending smile when we tell others what we do for a living. We deserve more than the micro aggressions of being compared to the yardstick of K-12 and falling short. We deserve to take pride in being the very first teachers of young minds, and knowing that the work we do makes a difference. But, it takes all of us to recognize that and to be a stronger voice in the educational community.